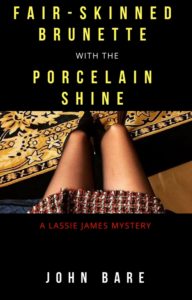

There is a fair-skinned brunette who curses in French

She winked at me once, from an old white Corvette

I showed her the stars, and she cried at Orion

We poured Lagavulin and sang Tammy Wynette

She hangs jeans on her hips

and sheets on the line

The fair-skinned brunette

with the porcelain shine

Chapter 2

Escovedo’s song stopped. Pig Farm was quiet.

Siler was back around the bar. He took up his usual spot, leaning on his right elbow. Drink in his left hand. Dumb look on his face. He believed patrons drank more from a bartender who was non-judgmental. Siler was the smartest dumb-looking guy I had ever seen.

Fats took up the stool beside me.

Clinked her glass into mine. She drank. I drank. Siler drank.

We all sat there and let the rye do the talking.

After 30 years, the extended silence seemed appropriate. The silence was more comfortable than conversation. One long moment, making the transition from then to now, from young to old, from old to new, from bulletproof to fragile, from looking out dreamily toward life’s horizon to walking up to the edge of life’s cliff.

“Thanks for the biscuit,” I said, finally turning toward her and catching my breath at the way she had aged into a captivating beauty. Fats was shimmering. Still.

“Play me one of yours,” she said, nodding toward the iPhone on the bar.

In the old days, I had been writing songs with several local bands. She always liked the secret knowledge of a lyric she had inspired.

I had kept at it over the years. For a long time, it was like I was playing a joke on myself. Kept writing songs on the side, but no one in the music business showed interest.

Then in the last 10 years or so, I started to get nibbles from the young bands and songwriters working East Nashville. The songs bounced around, and a couple of legends found them. I was beyond thrilled. I had written or co-written a dozen songs that made the final cut of some albums. But the agate print on songwriting credits is pretty abstruse stuff. Surprised Fats knew.

Siler was aware I was writing some songs, but I don’t think he could tell you much about which tunes were mine and which weren’t. Mostly, he liked the road trips to Nashville.

My song writing credits were under the name they both knew, Lassie James.

I worked the app and dialed up a Lyle Lovett tune I had co-written, “Brownsville Tonight.”

Buenos dias, mi amigo, have you seen my friend?

Have you seen the pretty girl who taught me how to sin?

Mexican topaz, she shimmers at night.

Her skin is electric and gives off white light.

How many stars in Boca del Rio? How many stars in old New Orleans?

How many stars in Nuevo Laredo? How many stars in Sweetwater Springs?

How many stars can fit in the sky?

How many stars in Brownsville tonight?

How many stars in Brownsville tonight?

“Congratulations,” Siler said, looking at Fats. “The ceremony tomorrow?”

“It’s Thursday,” she said. “Big la-di-da at McCorkle Place. Academic gowns, bunting and the works. Mostly an excuse to get back here. I’ve been away a long time.”

Every October 12th, the University celebrates the anniversary of the laying of the cornerstone of Old East Dorm, the oldest building at the oldest state university in the country. On the day of the annual celebrations, the university also presents awards to distinguished graduates.

This year, Fats would be among the alums up on stage being recognized.

Chancellor Sanders Mallette, who had been one of the great journalism professors before taking the administrative role, would be presenting the honor to Fats. The event would double as Mallette’s inauguration. He’d been named chancellor a couple of months back, put in place to clean up the world-class academic fraud scandal driven by an athletic department that had become a professional subsidiary of the university.

I had known Mallette since my sophomore year, when I was in his intro newswriting class. Then he had served as my doctoral adviser for the past three years, and he was still chairing my dissertation committee. I was scheduled to defend the dissertation next week. Assuming a successful defense on Monday, I would be in position to secure a Ph.D.

In between the old undergraduate days and returning to campus for grad school, Mallette became a friend and mentor, and something more. When I was on top – when I received the Pulitzer, when my name was above the fold in papers across Europe – I would get a call from Mallette. Always with gentle reminders to focus on service to others, ways I could give back.

Whenever things turned sour – when my fiancé ditched me in London, when the shrinking industry send me packing – he would always call with a boost. A new lead, a new opportunity. Somehow he knew. The man was blessed with timing.

When the Post offered another round of buyouts, another step toward self-immolation, Mallette called again, even before the news hit the wire. He knew. He always knew.

“We’ve got a spot for you here in Chapel Hill,” he said. “Come do the Ph.D. program, and then join us on faculty.”

I could teach and do free-lance writing gigs, he said.

“And you’ll have more time to write those hit songs,” he said. “You’ll be a man of letters, like Kristofferson.

Still waiting on the hit song. Otherwise, his forecast was true. With the buyout, the free-lance writing income and the surprise of modest songwriting royalties, I could afford a few afford luxuries. And a Ph.D. was a luxury. I never expected to teach sociology – or anything else. But I could check if off the bucket list.

Fats reached over and squeezed my hand.

“I love ‘Brownsville Tonight,’” Fats said. “I heard Lyle sing it at the White House last spring. The mandolin piece is incredible.”

Siler kept his dumb look. Bartenders don’t care about name dropping.

“But I was thinking of another one,” she said. “You know I always got weak in the knees when you wrote a line about me.”

I finished my rye. The bottle of Bulleit was draining. The whiskey was down below the bottle’s green label. Siler poured me more. Put a fresh bottle on the bar as back-up, the way a gunnery sergeant might set a spare magazine nearby when he senses the machine gun running low.

“You know the one,” she said, leaning her body sideways and bumping her shoulder into mine.

“There I am at the White House for a celebration of the American arts, and I have to hear it from John Prine. A woman needs to hear about that kind of song from the source.”

Siler looked like he might doze off.

I knew the song.

She knew me, still. How to get inside my head.

My fingers worked the app.

Prine growled on the juke box, singing about the “Fair-Skinned Brunette With the Porcelain Shine.”

My back shivered as Prine sang the lyrics I had imagined and written about the sexy girl I knew so long ago. I felt the hum of her heartbeat even from a distance and knew art was imitating life imitating art again.

“Welcome home,” I said, turning back her way and this time holding her eyes with mine. “I’d love to watch the leaves change with you.”

Fats reached for the bottle and emptied the rye into her glass.

“What are we gonna do ‘til sun up?” she asked.

Siler yawned.