She wears two shades of lipstick and never waits in line.

She carries mini-bottles, and a knife to cut up limes.

She’s the Queen of Whiskey Glam. Jack Daniel’s meet Kate Spade.

She always wins at Twister. She played the Turf back in the day.

Chapter 3

The rest of the world knew Fats as Dr. Holly Pike, the face of a new generation of scientists ready to transform global health.

After Fats walked out of Z-4, she moved to New York and began taking graduate classes at Columbia. As she had been at UNC, she was a star there.

At Columbia, Fats ultimately took a Ph.D. in chemistry and also a law degree. In her summer law firm work, she specialized in intellectual property.

My old girlfriend with the crooked bush started figuring out how to design and program cells to behave differently. She took patents on every innovation.

The big pharm companies all wanted her, and the law firms were fighting to get her. Federal agencies and global NGOs that fund scientific research wanted her to set up a lab that would focus on breakthrough public-health research.

She set up a lab at Columbia and created a one-of-a-kind center of applied research, intellectual property and public health.

At first, all of this made Fats a minor celebrity within a highly specialized, arcane field.

Then she designed a drug to grow hair. She became as famous as a Kardashian.

It wasn’t exactly a drug, she explained.

Siler queued up the juke box with Merle, George, Waylon, Kris and more Merle. The live version of “Yesterday’s Wine” always made Siler cry.

The FDA puts inventions into different categories.

First, there are devices. This includes everything from a Q-tip to a penile implant. Medical devices must be approved by the FDA, and the government tracks problems, recalls and so on. Huge business.

Second, there are drugs. Crestor, for example, is a one of the big-time drugs docs prescribe for folks who need assistance in lowering cholesterol levels. Another huge business.

Third, there are biologics. This is a kind of medicine built from living cells or biological source – not man-made chemicals. Humira, the arthritis medicine advertised on TV, is a biologic. Vaccines and gene therapy are examples of biologics. Over the next generation, this will become bigger business than devices and drugs combined.

“When I was a doc student, we would hang out at a pub in New York and laugh about the riches coming to the first person to find a cure for male-pattern baldness,” Fats said.

“Given that erectile dysfunction drugs are all over the market, a cure for baldness was the last cash cow out there for quality-of-life drugs. It seemed like a lark at the time. Then when I started the lab, I was grinding away on solutions for diseases in developing countries and seeking funding for cancer research and more. We have this incredible untapped potential to improve health – if we just had the funding. Up late one night, it hit me: Stop applying for funding and generate my own. So I pulled together a team and spent a year figuring out male pattern baldness.”

Once through the clinical trials, FDA red tape and so on, Fats was printing money. She owned the intellectual property and the rights to the science and was the sexy face of a cure millions of men wanted – and millions of women wanted for men.

From our old UNC connections, Fats linked up with Michael Jordan as the first pitchman. They created a Jennie Craig-style before-and-after campaign.

The most famous, richest, sexiest bald athlete on the planet emerged in the “after” TV commercials with a head of hair that could have landed him on The Mod Squad.

The treatment – a biologic – was marketed as Air Hair, through a new company that Jordan and Fats launched together.

On the day of the IPO, she became a billionaire, for the first time. Jordan became a billionaire again.

“I went from a prestigious but little-known research lab to TMZ cameras following me around with MJ,” she laughed. “Columbia didn’t know what to do.”

Through a series of trusts, private firms and publicly-traded companies, Fats organized a wealth-management strategy to fund a combination of public-health research and highly profitable designer medicines. Through what Time magazine called a virtuous spiral, Fats was making money faster than she could spend it – in the literal sense.

Money from putting hair on heads and other designer treatments was funding work that would rein in Ebola and was showing promising signs with cystic fibrosis and uterine cancer.

“It was like we kept having hit records. One biologic would hit, then another, then another. I started living well, even with whole streams of revenue carved off to fund my lab and the trusts. Crazy as it sounds, I outgrew Columbia.”

Fats described how she created a corporation with a sister organization – a foundation – with labs in Tokyo, Budapest, Lima, Cape Town, New York and Atlanta. Her ventures became so profitable she invited three rounds of debt and equity funding. She was over-subscribed each time.

Forbes doesn’t know where to put her on the list, but she’s in the top 400. And expected to be the top woman on the list next year.

Siler was wearing a ball cap with the logo from Goody’s headache powder. He lifted it and winked at Fats. He had a good half-inch of hair on the top of his head, bristly from a brush cut.

“And I thank you,” Siler said.

We were well into the second bottle of Bulleit.

A Tammy Wynette tune rolled up on the juke box. We both looked at Siler.

He shrugged.

“Guess we need to go check out Orion,” she said.

Fats opened the door and stepped out onto the back deck. The fall night had turned cold in Chapel Hill. Sky was clear. She pointed to the north.

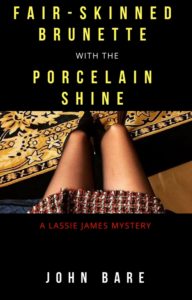

Fats was in a short sky-blue dress with tights underneath. Knee-high white boots. A leather jacket was on a hook by the pool table.

Her black hair hung past her shoulder blades. Until the wind blew it sideways.

“What do you have to eat around here these days?” she asked, putting the question to the heavens.

“Biscuits. I’ll go get some biscuits,” Siler said, heading down the back stairs to Time Out for a supply of chicken-and-cheese biscuits.

“Put on some hot water, too. I’d like to get some green tea going,” she said.

Fats came in off the porch, closed the door and picked up the pool cue. Her face was flushed from the wind, her eyes watery and sparkly. She leaned on the cue, using it as a cane to stabilize her from the whiskey, the cold and the memories.

“I have a job for you,” she said.