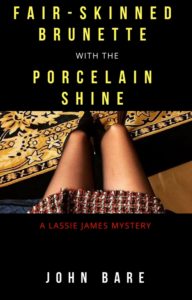

Chapter 1

There is a fair-skinned brunette, who grows her own okra

She wears a big hat, to keep her cheeks soft

Her shoulders get red, in the Halifax sun

She appears in my dreams, when angels carry me off

She hangs jeans on her hips

And sheets on the line

The fair-skinned brunette

With the porcelain shine

Monday night in October. Sitting at the bar at Pig Farm Tavern in Chapel Hill. 11:57 p.m.

Fats just walked into the bar.

I can smell the lavender in her hair. Most of all, I feel the crackle, as if her skin is spitting electric charges into the air. She walks into a room, and everything goes static. Even with my back to the place, I know she’s here.

I had been in deep conversation with the bartender, Siler, who is also the tavern owner and a very old friend. We were debating biscuits and gravy. These nouvelle cuisine chefs just don’t get the pepper seasoning right.

Now Siler is looking past me. Red flush runs up his neck, through his cheeks and into his temples. He picks up my glass of Bulleit Rye and finishes it.

I hear Fats racking up the pool table, rolling the nine-ball set back and forth over the felt.

“Siler,” she calls out, as casual as if she’d never left. “Pour me one of those.”

The crack of the break.

“In fact,” she goes on, “pour one for yourself. And a fresh one for Lassie. On me.”

There’s not another soul in the place.

Her cue pops again, and balls scramble around the table.

I am Lassie. My birth certificate, signed by a New Orleans doctor a half-century ago, reads Lassiter James Battle. Students at my high school in Saluda, on the edge of the Nantahala National Forest, knew me as James Battle. Later, that became my byline at the Post.

Fats, Siler and a handful of old friends from Chapel Hill dubbed me Lassie James. These were the folks who rode out the blistering heat of freshmen orientation week, which unfolded without air conditioning or inhibition.

Feels like that was a hundred years ago.

I guess it was closer to 30. Or 32? Useless to work out the math. We’ve all lost the energy for precision at this point. All that matters now is that we’re all rolling up on age 50, closer to death than to freshman year.

Last time I saw Fats she was naked as a baby. We had just graduated from the University of North Carolina. We were scheduled to leave Chapel Hill that day to elope, ready to drive to Vegas to start the rest of our lives as husband and wife.

In hindsight, I can tell you we were both hungover that morning. At the time, I didn’t know what a hangover was. Every morning felt that way, the only way.

We fell asleep after making love on the floor of apartment number Z-4 in the Old Well complex. Fell asleep right there on the shag carpet, tangled up in legs, wetness and a cotton quilt.

When the sunrise brought us into consciousness, Fats stood up, reached her hands toward the ceiling to stretch out the cramped muscles.

“My wedding day gift to you: I’m going to get biscuits,” she said.

Not a stitch of clothing on her. Long dark hair, light fair skin. Her nipples soft. Her ribs poking out. Eyes the color of brass cymbals. Freckles on her shoulders. Bright red lips wet like cranberry sauce against her pale skin. Her lips looked painted on.

As she stretched out her five-foot-two frame, uncoiling like a spring, I laughed a little to myself – noting yet again the grooming between her legs. Her attempts with the razor to trim the hair into a little strip were never spot on. The resulting artistic creation was a kind of crooked polygon.

On a similar morning a couple of years before, I couldn’t get over how the styling took the shape of the state of Minnesota. Which led to my calling her Fats. Which she took as me mocking her skills at the pool table.

I let her think that. The name stuck, at least among our intimate clutch of four or five college friends, Siler included.

So she became Fats.

And on that long-ago morning, I watched her beautiful naked ass walk around the corner to grab her jeans. Her skin seemed lit from underneath, some sheath of white light draped over her muscle and bone and her skin fitted over the illumination. I heard the door close and her car start. She was headed to Sunrise Biscuit Kitchen, a source of something both nutritional and medicinal. A bacon-egg-and-cheese biscuit and cinnamon roll were the only things that could sop up the booze still percolating through us.

I never saw her again. At least not in person. When Time magazine put Fats on the cover, claiming her medical research promised to save America, I saw her then. Plenty of times I saw her on TV. Then I saw her on red carpets with celebrity business partners.

She never came back to Z-4 that morning.

Three days later I received a package in the mail.

Inside was a bacon-egg-and-cheese biscuit and a cinnamon roll. Stale, banged up and beyond the sell-by date. But edible. So I sat alone in Z-4 and ate the days-old meal and stared at her note.

“I can get you the biscuit. I can’t marry you. I miss you, but I need to make a new adventure. On my own, for now. Let’s take the summer. Then meet up in the fall and watch the leaves change. I love you, Fats.”

That was the note. I threw it into the lake. We never met up. We never again watched the leaves change.

Fats was always the smart one.

I was crazy enough that I really would have eloped. She figured out we had been living in a bubble of undergraduate exuberance, delusion and indulgence. All of which was magical but none of which indicated we should or could build a life together.

So she ran away from me. And she made a life better than I could have given her.

I had probably done better, also – that is, better than I would have with her. I bopped around the globe on reporting assignments, without every worrying about a trailing spouse, and ended up with a Pulitzer citation on my wall. When the journalism business shrank, I moved on to free-lance writing and relocated back here to Chapel Hill to take a Ph.D. in sociology.

So no hard feelings, right?

The taste of stale biscuit rose in my throat.

Now she’s in Pig Farm with me, 10 feet behind me. Working the pool stick around the table and buying me rye whiskey.

Siler poured his. Poured mine. He came around from behind the bar and walked over to the pool table and set her glass down on a high-top table cluttered with chalk and postcards promoting live music shows.

I didn’t turn around. I could hear them speaking. Pausing to hug. Heard their glasses clink. Heard Fats be profane and Siler laugh loud enough to cover the music.

My iPhone was sitting on the bar. I punched up the TouchTunes app that let me control the juke box remotely.

Alejandro Escovedo’s voice boomed through the speakers. How he likes her better when she walks away.

“Lassie,” I heard her call out.

She waited. I drank my rye. I didn’t turn around. I didn’t speak.

Fats yelled: “Wanna hang out ‘til sun up and watch the leaves change?”

It was turning into a long night.